“If you have money, there’s support.” An autistic mother and son survive the maze

Despite little research on the challenges faced by autistic adults, the autistic community and self-advocates are on the frontlines of finding solutions

The weight of it all pressed down on Laura Dove like a physical force—the weight of knowing that while Medicaid might offer some support for autistic children, once they become adults, the lifeline essentially disappears, leaving families like hers adrift.

Exhausted, she lay in bed, staring at the ceiling, the fluorescent lights of the hospital room buzzing overhead. Her mind, usually a whirlwind of ideas and connections, felt sluggish, clogged. Words, once her weapon of choice, felt like heavy stones lodged in her throat. She couldn't speak, couldn't think, couldn't even seem to regulate her own breathing. This wasn't just fatigue. It was a deep, soul-crushing exhaustion born from years of battling a system that seemed designed to break her.

“If you have money, there’s support,” says Dove, who’s been using Medicaid and food stamps to survive over the last eight years.

While Medicaid provides some support for autistic children, that safety net vanishes for adults, leaving many without essential care. Misdiagnosed for years, Dove experienced repeated hospitalizations for what was labeled nervous breakdowns—when in reality, she was suffering from autistic burnout.

“There's no treatment for adult autism,” says Dove. “You need another condition.”

Co-occurring medical conditions are well-researched in children with autism spectrum disorder (ASD), while emerging evidence indicates that adults with ASD face higher rates of adverse physical health outcomes.

Adding to this concern, recent studies suggest a reduced life expectancy for adults with ADHD—a diagnosis also shared by both Dove and her son, Elliott.

The pursuit of support for Dove’s undiagnosed autistic son had taken its toll. By her bed, mountains of medical files, a seemingly endless stream of forms for schools and organizations, dead end after dead end. It all culminated in physical collapse.

Dove’s son, like many others, was initially diagnosed with ADHD. She spent years navigating a labyrinth of health and education systems, a journey that had taken a devastating toll on her own health, compounding with chronic illness.

This lack of support for autistic adults, however, is not confined to the United States.

The lack of support and services for autistic adults is a global issue. North of the border, autistic people face similar challenges in accessing services.

Last year, the Autism Alliance of Canada published a report Exploring the Needs of Autistic Adults in Canada. The survey was led by autistics, for autistics.

Autistic adults in Canada face significant challenges across multiple areas of life, with cost of diagnosis being one of the most common barriers to access. Financial vulnerability is also a major concern, as over a third of participants were unemployed at the time of the study. Many others rely on government disability assistance, which reflects broader trends of poverty among those on disability benefits.

Social isolation further compounds these difficulties, with nearly 90 percent of respondents reporting exclusion more than twice the rate seen among Canadians during the pandemic. This sense of disconnection poses serious health risks, including increased susceptibility to conditions such as dementia and heart disease.

The Autism Alliance of Canada’s study is ahead of the curve, as there is little research globally on services for autistic adults, including medical care and service delivery. Advocates are still fighting for international acceptance, rather than general awareness, as national autism strategies emerge to address systemic failures.

A 2022 study on autistic adult services in the European Union, part of the ASDEU project, echoed findings from the Autism Alliance of Canada. It highlighted the diverse needs of autistic adults in areas like housing, employment, education, and social services, with many struggling to access appropriate support. The study also revealed significant gaps in provider knowledge, including a lack of autism training among service staff, unawareness of wait times, and failure to meet established care recommendations. Addressing these gaps is crucial for improving service delivery and ensuring better support for autistic adults. Another 2022 study found that autistic adults experience lower-quality healthcare and poorer overall health outcomes.

The growing prevalence of autism diagnosis among young adults could signify the historical failings of screening and diagnostic criteria. It could also indicate systemic bias, how people mask their symptoms during childhood, throughout their youth, all the while being misdiagnosed and treated for other conditions.

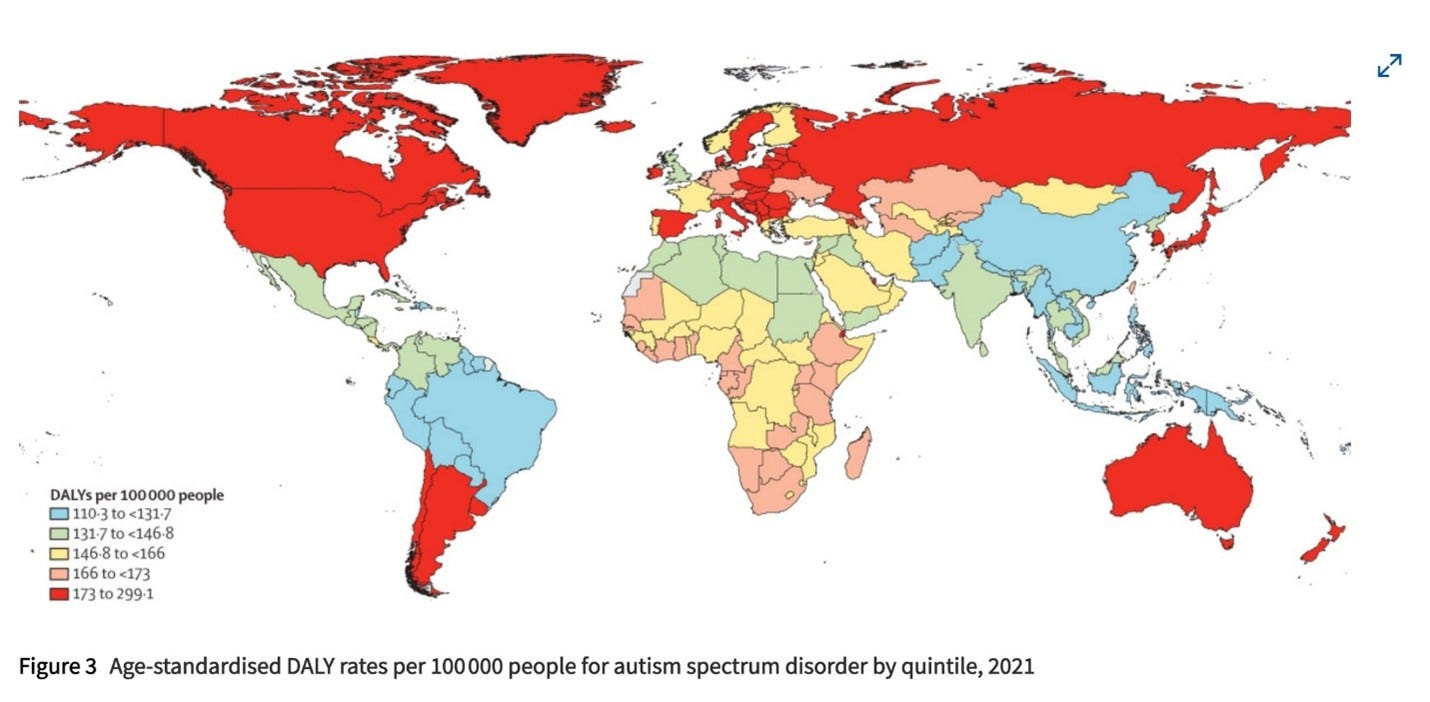

On a global scale, autism ranks among the top contributors to non-fatal health burden for people under the age of 20, according to groundbreaking findings from the Global Burden of Diseases, Injuries, and Risk Factors, published in December. This research shows how 61.8 million people worldwide—or about one in every 127—are autistic.

While Autistic people face a heightened risk of mental health challenges, self-injury, and suicidality, it wasn’t until 2018 that research first examined the treatment and support available to autistic adults for these same issues.

The rising rates of autism diagnoses across the US highlights the need for expanded healthcare services and further research into sociodemographic disparities within this growing population. Between 2011 and 2022, autism diagnoses among women surged by 315 percent, compared to a 215 percent increase among men.

Studies suggest that societal expectations around gender norms may contribute to women masking autistic traits, possibly due to social pressures and stigma. However, as awareness grows, more women and girls may feel empowered to seek a diagnosis. Changes in developmental screening practices, diagnostic criteria, policies, and environmental factors may all play a role in the increasing number of cases.

Falling Through the Cracks: The Maze to an Autism Diagnosis

For many families, the path to an autism diagnosis is not a straight line—it’s a maze full of dead ends, misdirection, and missed opportunities. For one mother, that reality became clear as she looked back on the signs she had overlooked in her own child.

“My child was missed by so many people, including me,” says Dove. “The DSM gives a very narrow description of autism, and if you don’t fit it, you’ll be overlooked.”

The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM) continues to evolve, with updates reflecting growing research and understanding of autism. However, many medical practitioners consider additional factors beyond the DSM, incorporating clinical judgment, patient history, and broader frameworks to better capture the diverse presentations of autism across different age groups and genders.

Even those who do fit the criteria sometimes go unnoticed because many psychologists and doctors still rely on outdated, surface-level assessments. For this reason, Dove’s sister was diagnosed a level three autistic when she was a toddler.

“My sister fits the classic definition of autism,” she says. “The delayed speech, difficulty with back-and-forth conversation, very obvious traits. But for those of us who mask, or also have ADHD, it’s not so clear.”

The challenge is compounded by the way autism has traditionally been studied.

“They’ve been looking at autism from the outside for so long,” she explains. “That’s finally starting to change, but awareness takes time. And the way they frame it—as a deficit—only makes it harder for people who don’t fit the stereotype.”

Lost in the System: The Fight for Autism Support After Diagnosis

For Dove, the battle for autism support services has been an uphill fight.

“When my diagnosis finally came, I thought things would get easier,” she says. “Instead, no support services were offered. Not for me. Not for my son. Nothing.”

Dove describes navigating a labyrinth of bureaucracy—contacting organizations, filling out extensive paperwork, trying to secure financial assistance.

Dead end, after dead end.

“The waitlists are long. There aren’t enough practitioners who understand autism. Organizations are overwhelmed, underfunded, and unable to keep up with demand.”

In the end, the system leaves autistic families to fend for themselves.

“Finding support takes so much footwork,” says Dove. “Even after all the effort I’ve put in, I still haven’t found anything sustainable. It all comes down to money.”

The Uphill Battle for an Education That Works

Finding the right school for a neurodivergent child can be an exhausting maze of trial, advocacy, and frustration. Dove faced this firsthand when her son Elliott was denied accommodations. She reached out to the school and hoped the administration would recognize the flaw in their approach. Instead, their response was dismissive.

Elliott struggled to keep up with academic expectations as the need for executive functioning increased while he progressed through high school. This led to severe mental health challenges for both mother and son.

Eventually, the school admitted they simply did not have the resources to support her son properly. Faced with a system unwilling to adapt, Dove looked into specialized schools for children with ADHD and autism, schools that prioritized building executive functioning skills. But the cost was staggering—$35,000 a year, on top of the $15,000 they were already paying for Catholic school.

Without financial support from her family, it simply wasn’t an option.

“I wish they had schools like that in the public system,” she says. “But they don’t.”

The challenges didn’t stop there. Her son was disciplined for behaviors tied to his autism—stimming, echolalia, simply existing in a way that didn’t fit the mold. Despite succeeding academically, he was still treated as a pariah. For many neurodivergent students, the biggest barrier to education isn’t their disability—it’s the system itself.

“I've heard this story so many times from other parents—how hard we have to fight to get basic accommodations, to make sure our children are being respected.”

In 2024, after bouncing from school to school, Elliott graduated from high school. He now studies sound engineering at Anne Arundel Community College in Maryland.

Dove remains deeply worried about the future, especially when it comes to healthcare access. Medicaid, which has been a lifeline for many neurodivergent people, faces an uncertain fate under shifting political leadership in the US.

"I'm worried about access to healthcare or any kind of government support," she says.

Yet, despite the fear, she also sees signs of hope. She says the autistic community is growing louder in its advocacy and pushing back against outdated perspectives.

NEW RESEARCH

Life expectancy and years of life lost for adults with diagnosed ADHD in the UK

Investigating deaths of autistic people in health and social care in England and Wales

AI-boosted virtual reality system to help autistic students improve social skills

CAMI systems further understanding of Autism Spectrum Disorders

New human brain atlas charts gene activity and chromosome accessibility

EVENTS & INITIATIVES

Canadian Autism Leadership Summit

Family Justice Council Guidance on Neurodiversity in the UK

Inaugural 2025 Davos Neurodiversity Summit During the World Economic Forum

February 11 Webinar: Early Diagnosis of Autism and Emerging Solutions