The Future of NeuroInclusion and SNF

Why Amrutha Rao created the Strategic NeuroInclusivity Framework for Canada and how it will maximize the potential of all people

Amrutha Rao’s autism was hidden behind the “gifted” label for most of her life.

In 2019, she immigrated to Canada and became a citizen. What shifted during the move was her relationship to masking her autism. Rao noticed while there were many ways she was treated differently when moving to Canada, many of the patterns remained the same.

“Different cultures, same shape,” says Rao.

“Neurodivergent people are celebrated for output and insight, if those gifts arrive neatly packaged. Difference is welcome until it requires the system to stretch. Then it becomes a fit issue, a tone issue, or a leadership concern.”

Despite strong qualifications and unique talents, many neurodivergent people are either unemployed or underemployed due to systemic barriers deigned for neurotypical norms. Traditional hiring practices such as ambiguous job postings and unstructured interviews often disadvantage neurodivergent candidates even when they possess the required skills and credentials. These outcomes are linked to environments which reward conformity to neurotypical communication and social expectations, limiting opportunities for capable individuals whose cognitive styles differ from traditional norms. This is one reason why Rao created the Strategic NeuroInclusivity Framework (SNF) for Canadian employers.

The framework is designed to embed inclusion operationally, structurally, and culturally. It provides practical ways to bring clarity, consistency, and support for diverse cognitive strengths into everyday workflows. The pilot, starting in February, already involves over 40 managers and their teams. The participants will have the opportunity to explore practical tools such as structured agendas, communication standards, onboarding templates, observation methods, and see how these initiatives integrate naturally into the work.

What is an SNF Imagineer?

SNF Imagineers help engineer the future state of inclusion by building, testing, and refining inclusive organizational systems in real work environments.

Neurodivergent employees are twice as likely to experience workplace stress and three times more likely to leave their jobs prematurely without proper supports.

This absence of support limits daily performance and career growth and contributes to a higher turnover rate. The costs of this are significant, with a lack of neuroinclusivity potentially costing millions in lost productivity annually.

Embedding inclusion into leadership practice and organizational systems anticipates barriers before they appear. This approach moves beyond episodic adjustments or case-by-case accommodations, making inclusion a consistent, measurable component of operational excellence.

The bulk of Rao’s academic training is in testing hypotheses by building and observing real world engineering systems. She applied the same approach used in cancer research to the design of inclusive organizational systems through SNF. The goal is to test inclusion as infrastructure by engineering and evaluating organizational systems in practice.

In structured and predictable settings, Rao generally did well. When expectations were sudden or unstructured, however, her capacity could drop quickly.

“I experienced periods of being unable to speak,” she says, “cognitive shutdown under stress, and sensory overload, especially in response to repetitive sounds.”

Despite this, she maintained very high grades in demanding academic environments.

Rao built a strong academic foundation across technology, marketing, and business management. She earned a Master of Technology in Industrial Biotechnology from the Shanmugha Arts, Science, Technology and Research Academy (SASTRA), followed by a Post Graduate Diploma in Management – Communications (PGDM-C) with a focus on Strategic Marketing and Communication from MICA, The School of Ideas. In 2021, she completed a Master of Business Administration at the University of Toronto’s Rotman School of Management, which equipped her with a global perspective and leadership skills in business strategy.

Her high performance made it easy for systems to assume she was fine.

It wasn’t until her third master’s degree, after receiving simple accommodations, when she realized how different her experience could be with minimal support. That moment led her to pay thousands of dollars for an adult autism assessment.

Educational and diagnostic frameworks often miss autistic people who compensate effectively, especially when giftedness is involved. The results helped her see how many of the challenges she had managed quietly were not personal failings, but predictable outcomes of systems built around narrow assumptions about how competence appears in systems deigned for others.

Understanding this made it clear that her experience reflected a broader systemic pattern rather than an individual anomaly. It turns out, when you perform well enough, she says, the system assumes you aren’t playing the game on “Hard Mode.”

Hiring practices and workplace cultures create barriers by rewarding the visible, fast, and easily legible while overlooking deep, high-resolution thinking. In recruitment, structured assessments and panel interviews are merit-based on paper, but they favor candidates who can present answers in the “expected” way, quickly and concisely.

“True inclusion is when people can show up as they are and have their contributions shape the work. It is a culture and a set of practices that anticipate difference rather than reacting to it as an anomaly. We need to stop asking neurodivergent people to fit into neurotypical shapes and start asking why those shapes were so small to begin with.”

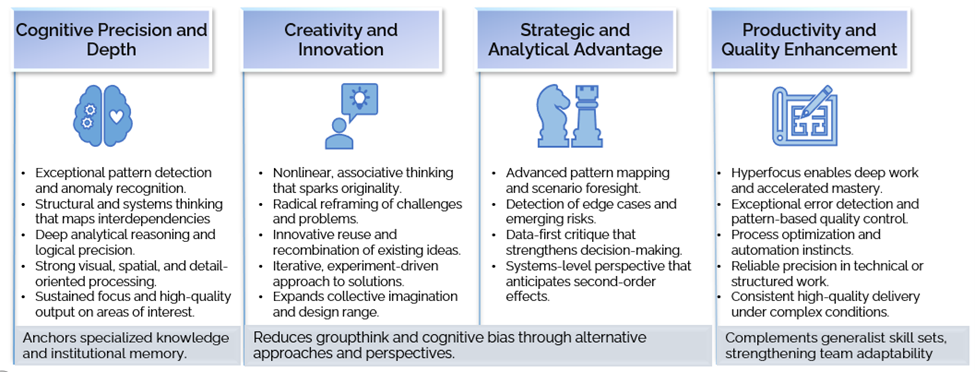

Neurodivergent strengths are central to this. People who notice hidden patterns, approach challenges from new angles, or see connections others miss, are often not given room to act on those insights. An inclusive approach looks like a culture where the person who identifies a hidden flaw in a plan is thanked instead of being labeled “difficult” or ostracized for bringing it to light. It is a space in which the need for coherence is seen as a commitment to logic, and precision is seen as an asset.

The SNF replaces ambiguity with predictable processes and clear structures, allowing people to contribute their best work without the exhaustion of navigating hidden social norms. From Rao’s perspective, creating structurally inclusive environments where all minds thrive, is the real work of leadership, not just delivering on outcomes.

Growing up gifted and autistic, Rao learned early how workplaces often reward speed and visibility while overlooking depth. She can notice patterns, anticipate challenges, and approach problems differently than many of her colleagues, but those abilities are only valuable if the system is wired to receive them. The SNF provides this interface. It allows the organization to leverage high-resolution thinking for collective impact and demonstrates how processes can be built for cognitive diversity.

“The SNF is my response to the inefficiency of office vibes,” says Rao, or in essence, creating a system which rewards capability over conformity to arbitrary social norms.

“My lived experience has shown me that ambiguity is the greatest enemy of equity,” she says. “When expectations are vague, the person who thinks differently is the first to be penalized for their personality rather than their results.”